Our International Saints

We are blessed to be a multicultural community sharing one faith. Let us all acknowledge and celebrate the patron saints and feast days of the saints particularly important to our community.

We have started with our Filipino brethren and hope to add other nationalities soon.

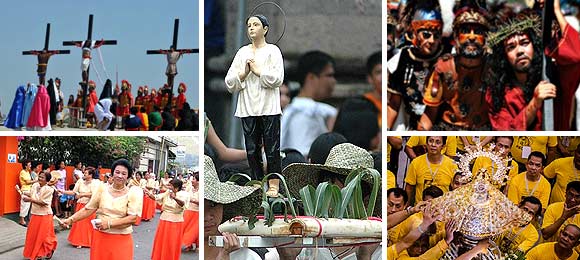

Fiestas in the Philippines are held to celebrate a patron saint (the Philippines is the only majority-Christian country in Southeast Asia) or to mark the passage of the seasons, depending on which part of the country you're in. The sole exception is Christmas, where the whole country breaks out in celebrations that can begin long before December.

The feast days and festivals include Feast of the Black Nazarene, Ati-Atihan Festival, Sinulog Festival, Moriones Festival, Panagbenga (Baguio Flower Festival), Maleldo Lenten Rites, Pahiyas, Obando Fertility Rites, Flores de Mayo, Peñafrancia Festival and Sambuklod Honors.

Filipino Community

and Prayers

Filipino Community

and Prayers

People from the Philippines are called Filipinos. There are different dialects all throughout the country but the most common one that everybody can be well understood is the Tagalog.

Here are some of our prayers we recite in our own native language, Tagalog.

Philippine Feast Days

Fiestas in the Philippines are held to celebrate a patron saint (the Philippines is the only majority-Christian country in Southeast Asia) or to mark the passage of the seasons, depending on which part of the country you're in. The sole exception is Christmas, where the whole country breaks out in celebrations that can begin long before December. The roots of Philippine fiestas go back even further - back to before the Spanish conquistadores arrived in the 1500s. In the old animistic culture, regular ritual offerings were made to placate the gods, and these offerings evolved into the fiestas we know today. A wonderful fiesta season means good luck for the rest of the year. For individual Filipinos, fiestas can be a way of supplicating the heavens or to make amends for past wrongs. In one place, penitents lash themselves with whips; in another, childless women dance on the streets hoping for the blessing of a child. Every town and city in the Philippines has a fiesta of its own; whatever time of the year it is, there's sure to be a fiesta going on somewhere!

Feast of the Black Nazarene Quiapo, Manila - January 9

Feast of the Black Nazarene Quiapo, Manila - January 9

The Black Nazarene is an antique hand-carved statue of Jesus Christ, which is brought out to the streets of Manila's Quiapo district to lead a huge procession of thousands of barefoot penitents, all massing around the rolling statue yelling "Viva Señor!"

Penitents believe that touching the statue will grant one a miracle in one's life; stories have been heard of diseases healed and personal problems solved after touching the blackened statue.

The carving is black, legend says, because the ship that brought it caught fire along the way; despite its charred state, it is a prized icon for Manila's faithful.

Ati-Atihan Festival Kalibo, Aklan - January 1-16

The Ati-Atihan Festival honours the "Santo Niño", or

Christ Child, but draws its roots from much older

traditions. Festival participants wear blackface and

tribal clothing to imitate the aboriginal "Ati"

tribespeople who welcomed a group of Malay datus fleeing

Borneo in the 13th century.

The Ati-Atihan Festival honours the "Santo Niño", or

Christ Child, but draws its roots from much older

traditions. Festival participants wear blackface and

tribal clothing to imitate the aboriginal "Ati"

tribespeople who welcomed a group of Malay datus fleeing

Borneo in the 13th century.

The festival has evolved to become a Mardi Gras-like explosion of activity - three days of parades and general merrymaking that culminate in a large procession. Novena masses for the Christ Child give way to drumbeats and the streets throbbing with dancing townsfolk.

On the last day, different "tribes" played by townsfolk in blackface and elaborate costumes take to the streets, competing for prize money and year-long glory. The festival ends with a masquerade ball.

Other festivals in the Philippines, like the Sinulog in Cebu and Dinagyang in Iloilo, are directly inspired by the Ati-Atihan.

Sinulog Festival, Cebu City - January 6-21

Like the Ati-atihan, the Sinulog Festival is another

Catholic festival honoring the Christ Child (Santo

Niño), with deeper pagan roots. The feast draws its

origin from an image of the Santo Niño gifted by

Ferdinand Magellan to the recently-baptized queen of

Cebu. The image was re-discovered by a Spanish soldier

amidst the ashes of a burning settlement.

Like the Ati-atihan, the Sinulog Festival is another

Catholic festival honoring the Christ Child (Santo

Niño), with deeper pagan roots. The feast draws its

origin from an image of the Santo Niño gifted by

Ferdinand Magellan to the recently-baptized queen of

Cebu. The image was re-discovered by a Spanish soldier

amidst the ashes of a burning settlement.

The feast begins with an early morning fluvial procession marking the arrival of the Spaniards and Catholicism. The procession follows after a Mass; "sinulog" refers to the dance performed by the participants in the big procession - two steps forward, one step back, it's said to resemble the movements of the river current.

Participants dance to the beat of drums, shouting "Pit Señor! Viva Sto. Niño!" as they move the procession along.

Moriones Festival, Marinduque - April 18-24

The province of Marinduque celebrates Lent with a

colorful festival commemorating the Roman soldiers who

helped crucify Christ. The celebrations begin on Holy

Monday, and end on Easter Sunday.

The province of Marinduque celebrates Lent with a

colorful festival commemorating the Roman soldiers who

helped crucify Christ. The celebrations begin on Holy

Monday, and end on Easter Sunday.

Townsfolk wear masks patterned after Roman soldiers, taking part in a masquerade dramatizing the search for a Roman centurion who converted after Christ's blood healed his blind eye.

The festivities coincide with the reading and dramatization of the Passion of Christ, re-enacted in different towns throughout Marinduque. Penitents can be seen whipping themselves in atonement for this year's sins.

Panagbenga (Baguio Flower Festival) Baguio City - February 26

The mountain city of Baguio celebrates its flower

season with - what else? - a flower fiesta! Every

February, the city holds a parade with floral floats,

tribal festivities, and street parties, with the scent

of flowers creating a unique signature for this

equally-unique celebration.

The mountain city of Baguio celebrates its flower

season with - what else? - a flower fiesta! Every

February, the city holds a parade with floral floats,

tribal festivities, and street parties, with the scent

of flowers creating a unique signature for this

equally-unique celebration.

The word "panagbenga" is Kankana-ey for "blooming season". Baguio is the Philippines' foremost centre for flowers, so it's only appropriate that the city's biggest festival centers around its chief export. Other festivities include a BAguio Flower beauty pageant, concerts at the local SM Mall, and other exhibits sponsored by the local government and foreign sponsors.

Maleldo Lenten Rites, San Pedro Cutud, San Fernando, Pampanga - April 17-24

Maleldo is best described as Extreme Lent: San Pedro

Cutud village in Pampanga celebrates what is perhaps the

bloodiest Good Friday spectacle in the world, as

penitents flagellate themselves with burillo whips and

have themselves literally nailed to crosses.

Maleldo is best described as Extreme Lent: San Pedro

Cutud village in Pampanga celebrates what is perhaps the

bloodiest Good Friday spectacle in the world, as

penitents flagellate themselves with burillo whips and

have themselves literally nailed to crosses.

The tradition began in the 1960s, as locals volunteered to have themselves crucified to seek God's forgiveness or blessings. Many more followed, with hundreds making the "panata" (vow) over the years. Today, both men and women undergo the excruciating ritual.

Pahiyas, Lucban, Quezon - May 15

The Pahiyas is Lucban's uniquely Technicolor way of

celebrating the feast of San Isidro, the patron saint of

farmers. Held to celebrate a bountiful harvest, the

Pahiyas brings forth parades and traditional games - it

also introduces an explosion of color through the rice

wafers known as kiping.

The Pahiyas is Lucban's uniquely Technicolor way of

celebrating the feast of San Isidro, the patron saint of

farmers. Held to celebrate a bountiful harvest, the

Pahiyas brings forth parades and traditional games - it

also introduces an explosion of color through the rice

wafers known as kiping.

Sheets of kiping are colored and hung from houses, each house trying to outdo the other with the color and elaborateness of their kiping displays.

Apart from the kiping, fresh fruit and vegetables are everywhere for the visitors to taste and enjoy. The rice cake known as suman is also everywhere on offer - even total strangers are welcomed into the houses in Lucban to enjoy the house's culinary offerings.

Obando Fertility Rites, Obando, Bulacan - May 17-19

The town of Obando plays host to a pagan fertility

ritual with a thin veneer of Catholicism laid over it,

involving penitents dancing on the streets in the hopes

that the saints will grant them their wish.

The town of Obando plays host to a pagan fertility

ritual with a thin veneer of Catholicism laid over it,

involving penitents dancing on the streets in the hopes

that the saints will grant them their wish.

The penitents push wooden carts before them bearing the image of the saint they wish to supplicate. The saint differs depending on what is being asked for - San Pascual Baylon for those who want a wife, Santa Clara de Assisi for those who want a husband, and our Lady of Salambao for those who want a child. The parade continues down the streets all the way to the town church.

Flores de Mayo, Nationwide - May

Communities throughout the Philippines celebrate the

Flores de Mayo, a month-long flower festival that honors

the Virgin Mary and retells the folk tale of the

rediscovery of the True Cross by Emperor Constantine's

mother Helena.

Communities throughout the Philippines celebrate the

Flores de Mayo, a month-long flower festival that honors

the Virgin Mary and retells the folk tale of the

rediscovery of the True Cross by Emperor Constantine's

mother Helena.

The highlight of any Flores de Mayo celebration is the Santacruzan, a religiously-themed beauty pageant featuring the community's most beautiful (or well-born) ladies marching in a procession through town.

Participants are dressed in the finest traditional clothing, but no one is better dressed than the lady who represents Queen Helena, who walks under a canopy of flowers. She precedes a float bearing an icon of the Virgin Mary. After proceeding to Church, the whole town celebrates with a huge feast.

For several years, some towns held gay Santacruzan parades, until a cardinal put the kibosh on that trend. ("Cardinal Bans Gays in Santacruzan", CBCPnews.)

Peñafrancia Festival, Naga City - September 19

A nine-day fiesta honors Our Lady of Peñafrancia in

Naga City, Bicol. The celebrations revolve around a

statue of the Lady, which is carried by male devotees

from its shrine to the Naga Cathedral. The nine days

that follow are Naga's biggest party - parades, sports

events, exhibitions, and beauty pageants vie for

visitors' attentions.

A nine-day fiesta honors Our Lady of Peñafrancia in

Naga City, Bicol. The celebrations revolve around a

statue of the Lady, which is carried by male devotees

from its shrine to the Naga Cathedral. The nine days

that follow are Naga's biggest party - parades, sports

events, exhibitions, and beauty pageants vie for

visitors' attentions.

On the last day, the statue is brought back to the shrine via the Naga River, on a fluvial procession illuminated by candlelight.

Sambuklod Honors, San Lorenzo Ruiz, Bulacan City - September 21, 2009

Sambuklod is an acronym which stands for “Sambayanang

Buhay at Umuunlad Kasama si Lorenzong Dakila.” (A

Community that is Alive and Growing along with the

Companionship of the Venerable Lorenzo).

Sambuklod is an acronym which stands for “Sambayanang

Buhay at Umuunlad Kasama si Lorenzong Dakila.” (A

Community that is Alive and Growing along with the

Companionship of the Venerable Lorenzo).

“Buklod”, a Tagalog word which means “unite” is what the festival hopes and wants to achieve - UNITY amidst DIVERSITY as a new parish and as a new and emerging community with residents coming from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds.

The annual festivity is held at San Lorenzo Ruiz de Manila Parish in San Jose del Monte, the First City of the Province of Bulacan under the guidance of its parish priest, Rev. Fr. Mario Jose C. Ladra (editor of the prayer book, “Straight From the Heart: A Prayer Companion,” a national bestseller). It starts with a Novenario (9 days Novena to San Lorenzo Ruiz). The days that follow are filled with activities like variety shows, singing contests, “Palarong Pinoy”, fireworks display, processions and a Grand Healing Mass. The festival culminates on the 4th Sunday of September with a concelebrated Mass and thereafter, a grand Parade and a Street Dancing Competition.

In celebration of the 8th Sambuklod Festival this year, mural paintings in the church interior will be blessed by the Most Rev. Jose Oliveros Jr., D.D., Bishop of Malolos on Sunday, September 27, 2009, the Feast of San Lorenzo Ruiz. Thousands of devotees, participants, sponsors and donors, and fun-loving fiesta goers are invited and expected by the parishioners and residents alike.

From the birth and conception of Sambuklod in 2001 and how the festival evolved and was celebrated with a different theme each year, this is a showcase and highlight of the community’s joyful and colorful thanksgiving for the many blessings received through the intercessions of San Lorenzo, the first Filipino Saint; the saint who had been willing “to live and give a thousand lives for God.” And as many Filipino believers and devotees had put it in their own words, “Si San Lorenzo ang Santong Madaling Lapitan, Huwaran ng Mga Pinoy Kahit Saanman.

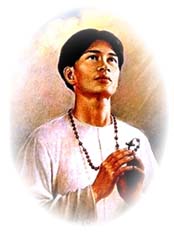

About Pedro Calungsod

Blessed Pedro Calungsod (c. 1654 – April 2, 1672) was

a young Roman Catholic Filipino sacristan and missionary

catechist, who along with Spanish Jesuit missionary

Blessed Diego Luis de San Vitores, suffered religious

persecution and martyrdom on Guam for their missionary

work in 1672. Calungsod was beatified on March 5, 2000

by Blessed Pope John Paul II. On February 18, 2012, Pope

Benedict XVI officially announced at Saint Peter’s

Basilica that Calungsod will be canonised on October 21,

2012.

Blessed Pedro Calungsod (c. 1654 – April 2, 1672) was

a young Roman Catholic Filipino sacristan and missionary

catechist, who along with Spanish Jesuit missionary

Blessed Diego Luis de San Vitores, suffered religious

persecution and martyrdom on Guam for their missionary

work in 1672. Calungsod was beatified on March 5, 2000

by Blessed Pope John Paul II. On February 18, 2012, Pope

Benedict XVI officially announced at Saint Peter’s

Basilica that Calungsod will be canonised on October 21,

2012.

Very little is known about Pedro Calungsod. Historical records never mentioned his exact place of origin or who his parents were. He was merely identified as a teenage native of the Visayas in the Philippines. Historical research identifies Ginatilan in Cebu, Hinunangan and Hinundayan in Southern Leyte, and Molo district in Iloilo as probable places of origin. Loboc in Bohol also makes a claim.

Moreover, no one even really knows how Calungsod looked like. Calungsod is often depicted as a young man wearing a camisa de chino. He holds the martyr’s palm, indicating his death, or sometimes a crucifix, catechism book or rosary, representing his missionary work.

Few details of his early life prior to missionary work and death are known. It is probable that he came to one of the schools run by Jesuits, where he learned Catechism and Spanish language.

Nevertheless, we can be certain of Calungsod’s ecclesiastical provenance since the entire Visayas region was under the old Diocese (now Archdiocese) of the Most Holy Name (Cebu).

MISSIONARY WORK

Pedro was just one of the boy catechists who went with San Vitores from the Philippines to the Ladrones Islands in the western North Pacific Ocean in 1668 to evangelize the Chamorros, according to www.pedrocalungsod.org. In that century, the Jesuits in the Philippines used to train and employ young boys as competent catechists and versatile assistants in their missions. The Ladrones at that time was part of the old Diocese of Cebu.

Calungsod, then around 14, was among the young exemplary catechists chosen to accompany the Jesuits in their mission to the Ladrones Islands (Islas de los Ladrones or “Islands of Thieves”). Around 1667, these were later named Marianas (Las Islas de Mariana) in honor of Queen Maria Ana of Austria who supported the mission.

Life in the Ladrones was hard. The provisions for the Mission did not arrive regularly; the jungles were too thick to cross; the cliffs were very stiff to climb, and the islands were frequently visited by devastating typhoons. Despite the hardships, the missionaries persevered, and the Mission was blessed with many conversions. The first mission residence and church were built in the town of Hagåtña in the island of Guam.

MARTYRDOM

According to Jesuit Martyrs in Micronesia written by Francis X. Hezel, SJ, the Jesuit mission in the Mariana Islands was the first in Oceania; it soon also proved to be one of the bloodiest. On 15 June 1668, San Vitores and a band of five other Jesuits arrived on Guam, the southernmost and largest island in a cordillera of fifteen volcanic islands. With the missionaries came a garrison of thirty soldiers, many of them colonials from the Philippines, whose responsibility was to protect the missionaries and to pacify the local people if need should arise.

At this time, Spanish missionaries were actively converting Chamorros to Roman Catholicism. This relationship was peaceful at the beginning with the Spaniards, who were led San Vitores. The initial reception of the missionaries by the Chamorro people was enthusiastic and reassuring. However, that changed over time when Chamorros grew resentful of the way their language and other customs were being replaced. Chamorro deaths had also increased due to foreign-borne illnesses. (www.guampdn.com)

Very soon, a Chinese quack, named Choco, envious of the prestige that the missionaries were gaining among the Chamorros, started to spread the talk that the baptismal water of the missionaries was poisonous, www.pedrocalungsod.org explained. And since some sickly Chamorro infants who were baptized died, many believed the calumniator and eventually apostatized. The evil campaign of Choco was readily supported by the Macanjas who were superstitious local herbal medicine men, and by the Urritaos, the young native men who were given into some immoral practices. These, along with the apostates, began to persecute the missionaries, many of whom were killed.

The most unforgettable assault happened on April 2, 1672, Saturday just before the Passion Sunday of that year. At around seven o’clock in the morning, Pedro – by then already about seventeen years old, as can be gleaned from the written testimonies of his companion missionaries – and San Vitores came to the village of Tomhom [Tumhon; Tumon], in Guam. There, they were told that a baby girl was recently born in the village; so they went to ask the child’s father, named Matapang, to bring out the infant for baptism. Matapang was a Christian and a friend of the missionaries, but having apostatized, he angrily refused to have his baby christened.

Meanwhile, despite the growing distrust and animosity between Chamorros and the Spanish, San Vitores and Calungsod visited Matapang’s home and baptized Matapang’s daughter. It is unclear whether San Vitores came unannounced or if he had been invited into the home by Matapang’s wife.

To give Matapang some time to cool down, Padre Diego and Pedro gathered the children and some adults of the village at the nearby shore and started chanting with them the truths of the Catholic Faith. They invited Matapang to join them, but the apostate shouted back that he was angry with God and was already fed up with the Christian teachings.

Determined to kill the missionaries, Matapang went away and tried to enlist in his cause another villager, named Hirao, who was not a Christian. At first, Hirao refused, mindful of the kindness of the missionaries towards the natives; but, when Matapang branded him a coward, he got piqued and so he consented.

When Matapang learned of the baptism, he became even more furious. He violently hurled spears first at Pedro. The lad skirted the darting spears with remarkable dexterity. Witnesses said that Pedro had all the chances to escape because he was very agile, but he did not want to leave Padre Diego alone. Those who personally knew Pedro believed that he would have defeated his fierce aggressors and would have freed both himself and Padre Diego if only he had some weapon because he was a valiant boy; but Padre Diego never allowed his companions to carry arms. Finally, Pedro got hit by a spear at the chest and he fell to the ground. Hirao immediately charged towards him and finished him off with a blow of a cutlass on the head. Padre Diego could not do anything except to raise a crucifix and give Pedro the final sacramental absolution. After that, the assassins also killed Padre Diego.

Matapang took the crucifix of Padre Diego and pounded it with a stone while blaspheming God. Then, both assassins denuded the bodies of Pedro and Padre Diego, dragged them to the edge of the shore, tied large stones to their feet, brought them on a proa to sea and threw them into the deep. Those remains of the martyrs were never to be found again.

The companion missionaries of Pedro remembered him to be a boy with a very good disposition, a virtuous catechist, a faithful assistant, a good Catholic whose perseverance in the Faith even to the point of martyrdom proved him to be a good soldier of Christ. (www.pedrocalungsod.org)

BEATIFICATION

A year after the martyrdom of San Vitores and Calungsod, a process for beatification was initiated but only for San Vitores. Political and religious turmoil, however, delayed and eventually killed the process. In 1981, when Agaña was preparing for its 20th anniversary as a diocese, the 1673 beatification cause of Padre Diego Luís de San Vitores was rediscovered in the old manuscripts and taken up anew until Padre Diego was finally beatified on October 6, 1985. It was his beatification that brought the memory of Pedro to our day.

Beatification is the act by which the Church, through papal decree, permits a specified diocese, region, nation, or religious institute to honor with public cult under the title “Blessed” a Christian person who has died with a reputation for holiness.

In 1994, then Cebu Archbishop Ricardo Cardinal Vidal asked permission from the Vatican to initiate a cause for beatification and canonization of Pedro Calungsod. In March 1997, the Sacred Congregation for the Causes of Saints approved the Acta of the Diocesan Process for the Beatification of Pedro Calungsod. That same year, Cardinal Vidal appointed Fr. Ildebrando Jesus A. Leyson as vice-postulator for the cause and was tasked with the compilation of a Positio Super Martyrio to be scrutinized by the Sacred Congregation for the Causes of Saints in Rome. The positio, which relied heavily on the documentation of San Vitores’s beatification, was completed in 1999.

Blessed John Paul II, wanting to include young Asian laypersons in his first beatification for the Jubilee Year 2000, paid particular attention to the cause of Calungsod. In January 2000, he approved the decree super martyrio (concerning the martyrdom) of Calungsod, setting his beatification on March 5, 2000 at Saint Peter’s Square in Rome. (www.wikipedia.com)

SAINTHOOD

On December 19, 2011, the Holy See officially approved the miracle qualifying Calungsod for sainthood by the Roman Catholic Church. The recognised miracle dates from 2002, when a Leyte woman who was pronounced clinically dead by accredited physicians two hours after a heart attack was revived when a doctor prayed for Calungsod’s intercession.

Cardinal Angelo Amato presided over the declaration ceremony on behalf of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints. He later revealed that Pope Benedict XVI approved and signed the official promulgation decrees recognising the miracles as authentic and worthy of belief. The College of Cardinals were then sent a dossier on the new saints, and they were asked to indicate their approval. On 18 February 2012, after the Consistory for the Creation of Cardinals, Cardinal Amato formally petitioned Pope Benedict XVI to announce the canonization of the new saints. The Pope set the date for 21 October 2012 (World Mission Sunday).

After Saint Lorenzo Ruiz, Calungsod will be the second Filipino declared a saint by the Roman Catholic Church. The Roman Catholic calendar of Martyrology celebrates Calungsod’s feast along with Blessed Diego Luis de San Vitores every 2 April. (www.wikipedia.com)